Introduction

In the future, there will be a greater need for international forest products in Central America due to increasing population size, deforestation, and tourism. According to Salamone (2000), “the United States forest product companies have overlooked Central America as an opportunity to expand their markets.” Due to improvements in health care, sanitation and education the Central American population has almost quadrupled from 11 million in 1950 to 40 million in 2008 (Fox 1990; World Bank 2010).

Deforestation has been and continues to be a major issue today for all Central American countries. The Panamanian government removed Law No. 7 that provided tax incentives for landowners to reforest their properties. This removal resulted in illegal logging and a decrease of reforestation projects (Munoz 2007). The natural forests of Costa Rica have been exploited due to shortages of wood for housing and furniture (Montagnini et al 2003).

Even in a global recession, tourism has been growing in Central American countries. Nicaragua had an 11% increase in tourists in the first five months of 2009 (Rogers 2009) and in the first year of breaking ground for the expansion of the canal in 2007, Panama has experienced an 11.2% increase in investment for tourism. Another example is Ecotourism, that has played a big part in Central America’s tourism trade since 8% of the world’s animal and plant species live in Central America (Schieber 2009). More wood products will be needed as tourism increases in Central America; a shortage of hotel rooms was observed in 2007 due to a 19% increase in tourism since 2005 (Fallas 2008).

The purpose of this research is to evaluate potential market opportunities for Virginia forest product companies in Central America.

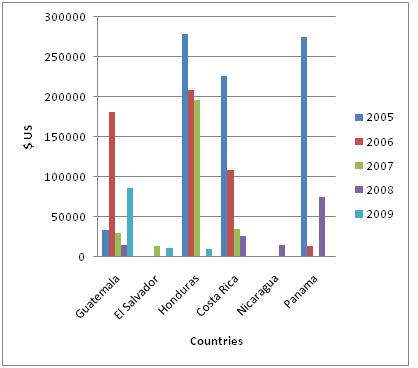

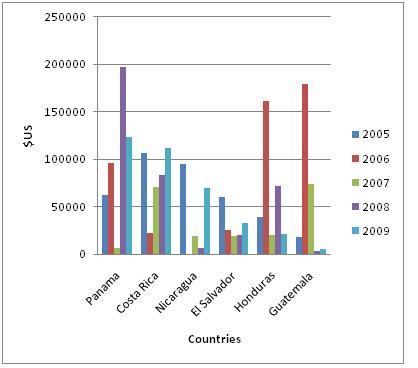

Virginian forest product companies have reduced the amount of wood products and furniture exported to Central American countries (Figures 1 and 2) because past unstable financial markets, higher freight rates, tighter credit lines, and soft housing markets (VDACS 2008). The North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) for wood products manufacturing (321) and furniture and related products manufacturing (337) exported from Virginia to Central America is shown is Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

In 2009, Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras were the only Central American countries importing wood products from Virginia (Figure 1). Most Central American countries increased in amount of furniture and furniture parts being imported from Virginia in 2009, except for Panama (Figure 2).

In spring 2010, the research team from Virginia Tech visited top forest product importers in Panama and Costa Rica. The objectives for the visit were to (1) investigate local production, (2) investigate local demand, (3) identify potential trade barriers, and (4) look into the future demand and production for wood products.

Methods

Personal interviews were conducted with Costa Rican and Panamanian forest product companies, and governmental and non-governmental agencies. Two questionnaires were developed from secondary research of the Central American forest product market.

Results

The Costa Rican and Panamanian governmental officials stated that their governments do not promote the use of wood products in their country. Due to lack of government support the state of the forest products industry in Panama has declined since 1993 and today only 5 companies exist with more than 50 employees in Panama. The forests are owned by the government and a request to harvest must be submitted to the Panamanian forestry agency. Most of the land available for planting high valued timber species has disappeared because of urbanization. The remaining available land has poor quality soils and is not sufficient for planting.

The wholesalers interviewed in both countries had 100-500 employees on average, with one wholesaler with over 2,000 employees. The wholesalers’ wood product lines currently consists of cabinets, flooring, furniture, millwork, and home improvement items. Their customer, base which primarily uses insect and decay resistant cement and steel, consists of retailers, homeowners, contractors, and government offices. Historically these items have been preferred building materials because of the hot and humid climate in Central America, but cement and steel require a lot of energy and produce large amounts of carbon dioxide and other pollutants during the manufacturing process. The Costa Rican Government has mandated that the country be carbon neutral by 2021; this gives wood product companies an opportunity to expand more into building construction.

The companies interviewed largely import pressure treated lumber, softwood lumber (10-15 containers/month), panels (1-10 containers/month), hardwood veneer (1-10 containers/month), flooring, and furniture/parts (1-10 containers/month). Some of the wood product wholesalers conducted business with wood product brokers in the U.S. for softwood lumber (Southern yellow pine) and panels, but all of the buyers were familiar with Southern yellow pine lumber from the United States. The companies in Panama and Costa Rica primarily import softwood lumber from Chile (See Figure 3), Brazil, Honduras, and Uruguay, which is dried to 12-14% moisture content. Imported panel products consist of oriented strand board (OSB), plywood, medium-density fiberboard (MDF), particle board, and B-B plywood; Oiled face & Edge-Sealed edges (BBOES) plyform.

The majority of the buyers were familiar with Appalachian hardwoods and they were willing to import them if they were competitively priced with native tropical hardwood species in the region. Appalachian hardwoods can be used in doors, mouldings, cabinets, furniture, flooring and ceiling panels. Flooring and furniture are primarily manufactured by using dark reddish species, therefore, black cherry (Prunis serotina) and black walnut (Juglans nigra) from the Appalachian region could be a substitute for the tropical hardwood species currently used, such as Guanacaste (Enterolobium cyclocarpum) (Figure 4).

- Transportation issues were addressed during the interviews. Wholesalers reported that logistics was not a problem when importing wood products. Products arriving to Panama primarily enter the country at the Panama City port. In Costa Rica, the products can arrive at two locations: Caldera Port, Puntarenas on the Pacific coast and Port of Limón on the Caribbean coast.

- Conclusions

This research supports the claim that United States forest product companies have not put enough effort into entering the forest product market in Panama and Costa Rica. Main conclusions indicate that the majority of the general public is unfamiliar with the properties and uses of wood as a building material since steel and cement are the currently preferred building materials. Forests in Panama and Costa Rica are not being harvested and the industry lacks support from the government, causing a reduction in the amount of raw material and production. An outside source of wood is needed to meet the needs of a growing region infrastructure.

References

Fallas, H. 2008. Country Caters to Tourists with Tight Supply of Rooms. La Nacion. Section of Economy. March 10. Available at: http://www.nacion.com

Montagnini, F. et al. 2003. Enviornmental Services and Productivity of Native Species Plantations in Central America. XII World Forestry Congress, 2003. Quebec City, Canada.

Munoz, M. 2007. Menejo Forestal en Panama. La Presna. November 25, 2007. Available at http://biblioteca.presna.com/contenido/2007/11/25/25-portada1.html

Quesada, H., R. L. Smith & J. Stopha 2009. Market Opportunities for Virginia’s Wood Products in Central America. Federal-State Marketing Improvement Program Grant.

Rogers, N. 2009. Tourism Grows Despite Worldwide Slump. The Nica Times. July 24-30, 2009. Available at:http://www.nicatimes.net/nicaarchive/2009_07/0724091.htm

Salamone A. 2000. Opportunities in Central America. Available at: http://www.fas.usda.gov/ffpd/wood-circulars/jun00/camerica.pdf

Schieber, B. 2009. Guatemala at The International Tourism Trade Fair, FITUR 09. The Guatemala Times. January 28, 2009.

Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (VDACS), 2008. Virginia Forest Products Export News. Fall-Winter 2008. Available at: http://www.vdacs.virginia.gov/international/pdf/forestnews.pdf

Virginia Economic Development Partnership (VEDP), 2008. Wood Products In Virginia. Available at: www.yesvirginia.org

World Bank, 2010. Country Data Profile. The World Bank Group. Available at: http://ddp-ext.worldbank.org/