By Johanna Madrigal, Phd Candidate

Virginia Tech

Email: jmadriga@vt.edu

Measuring innovation is a very complex process (Secretary of Commerce, 2007) for the private and public sectors. The Oslo Manual (OECD 2002 and 2005) suggests a methodology to measure innovation based on two sets of guidelines to define what activities belong to innovation processes and how to measure them. The first set of guidelines proposes that innovation activities should be previously segregated in three large groups in order to be measured:

- Research and Development (R&D) activities,

- process and product innovation activities; these activities include, but not limited to acquisition of external knowledge, machinery, equipment and other capital goods, and other preparation activities, and

- preparation for marketing and organizational innovation, covering all activities related to organization innovation other than R&D, such as, training, activities related to development and planning of new marketing methods and marketing instruments and the design of form and appearance of products (OECD, 2005).

The second set of guidelines is known as the Frascatti Manual (OECD, 2002) gives guidance on how to collect relevant data related to R&D activities, which are complemented by economic indicators developed by countries.

Now days, the United States government measures innovation activities based on data collected from two main reports developed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). These reports are:

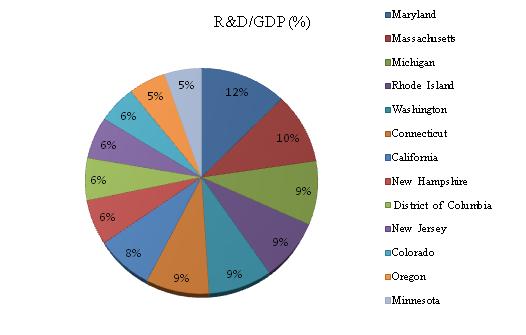

- the Science and Engineering Report which records the national volume of science and technology. Main indicators obtained from this set of data are the current status of R&D as a share of GDP and the R&D expenses per type or research; and

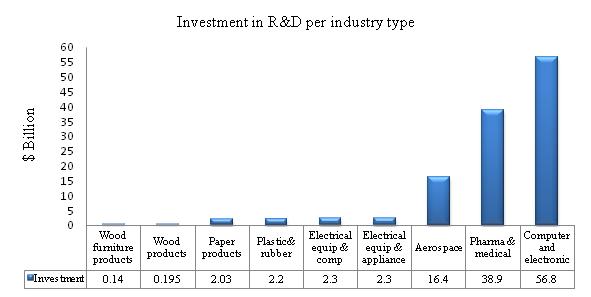

- (2) the Business R&D and innovation survey that collects the data relevant to Research and Development in the industry, where the main indicator reflects the expenditure in R&D made by different business sectors and the ratio of R&D to sector sales.

These two reports have helped to develop economic indicators such as R&D expenditure as a share of the GDP, R&D expenditure per type of expenditure and the amount of patent and scientific and research article generated among others.

At the industry level, literature research about innovation measurement suggest that there is no standardize method to define innovation metrics, however, there is a clear agreement about the importance to measure innovation to show firms’s growth (Anthony et all 2007, Kuczmarski 2001, Muller et all, 2005). Managers around the world recognize that measuring innovation will help to make informed decisions based on real data and, also, will help on the strategies and action plans alignment for successful results (Muller et all, 2005).

There are numerous authors who recommended several innovation metrics inside companies, such as Anthony et all (2007) who suggested a mix of metrics divided in three phases:

- In-put related measures

- process and oversight metrics; and

- output related metrics.

Also, McKinsey Global Surveys (2008) found out that business organizations are interested in using metrics across the whole innovation process, such as the number or people dedicated to innovation, the amount of new ideas from outside the company, the accomplishment of time schedule, financial returns from innovation, and customer service. In addition to the previous proposed innovation measurements for business organizations, the Boston Consulting Group (BCG 2008) also performed a study that found out metrics for four main factors. (1) start-up costs, (2) speed, (3) scale and (4) support costs

In summary, data available for further analysis about innovation at the industry level is quite limited (Secretary of Commerce, 2007), and mainly relies in the data collected by the U.S. government through the economic indicators as previously cited, and data collected by private organizations, such as McKinsey Global Surveys (2008), BCG (2008) and BCG (2009). Some of the metrics identify by these organizations are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Innovation metrics (Adapted from BCG 2009)

| Innovation phases |

| Metrics |

Inputs |

Processes |

Outputs |

| Number of new ideas

Business-unit investment by type of innovation

R&D ratio to company sales

Full time innovation technical staff |

Idea generation time

Decision to launch time

Projects by type and launch date

Projects NPV |

Patents granted

Launches by business area

Percentages of sales and growth from innovation projects

Innovation ROI |

With this quick review, the author aims to summarize findings from the literature to give a general overview about innovation measures at the public and private sectors. However the innovation process is rather dynamic as new metrics and measuring tools are continuously being developed.

References

Anthony, S., Fransblow, S., and Wunker, S. (2007). Measuring the black box. CEO Magazine. December (2007), 48-51.

BCG (2008). Measuring Innovation 2008. Squandered Opportunities. Massachusetts: US. Boston Consulting Group, Inc.

BCG (2009). Measuring Innovation 2009. The need for action. Massachusetts: US. Boston Consulting Group, Inc.

Kuczmarski, T. (2000). Measuring your return on innovation. Marketing Management. 9 (1), 24-32

McKinsey Global Surveys. (2008). Assessing innovation metrics. New York: US. McKinsey and Company.

Muller,A., Välikangas, L. and Merlin, P. (2005). Metrics for innovation. Guidelines for developing a customized suite of innovation metrics. Strategy and leadership. 33 (1)

OECD. (2002). Fascati Manual. Proposed standard practice for surveys on research and experimental development. Paris:France. OECD Publication Service.

OECD. (2005). Oslo Manual, the measurement of scientific and technological innovations. Paris:France. OECD Publication Service.

Secretary of Commerce. (2007). Innovation measurement: tracking the state of innovation in the American Economy. Washington, DC: US. US Department of Commerce.