by Gaurav Kakkar. Email at kakkarg@vt.edu

Performance is the crux of any business and strategic management is the epicenter governing that performance and creating value for customers, owners and stakeholders. Strategic management is the way managers funnel firm’s functions and actions to fulfil market demand. It is a framework to assess internal and external factors to a firm, integrate activities to learn, adapt and create value both in present and into the future (Amason, 2011). It can be defined in multiple ways. Chandler (1962) defines it as “the determination of the basic long-term goals and objectives of an enterprise, and the adoption of courses of action and the allocation of resources necessary for carrying out the goals”. According to Andrews (1987), strategy is the “pattern of objectives, purposes or goals and the major policies and plans for achieving these goals, stated in such a way as to define what business the company is in or is to be in and the kind of the company it is or is to be”. Both these definitions concentrate on the enterprise itself while defining the strategy. Hofer & Schendel (1978) incorporated external factors while defining the strategy as “the fundamental pattern of present and planned resource deployment and environmental interactions that indicate how the organization will achieve its objectives”. According to Kenichi Ohmae (1982), business strategy is all about competitive advantage with the purpose to “enable a company to gain, as efficiently as possible, a sustainable edge over its competitors”. Gilbert et. al. (1988) defined business strategy as “a set of important decisions derived from a systematic decision making process, conducted at the highest levels of the organization”. And the most recent explanation in the list of prominent attempts to define strategy was by Hoskisson et. al (2008). According to them, it is “an integrated and coordinated set of commitments and actions designed to exploit core competencies and gain competitive advantage”. While these definitions vary in approaches and perspectives, they all describe creation of superior value to achieve competitive market advantage by a firm. Strategic management thus aim at positing the firm within an attractive and manageable environment making it a unifying force guiding the firm to success in the competitive environment. But the next question would be how can the management of Forest products industry in the United States can use these definitions and design their own strategies. The following section of this article discuss prominent theories of strategic management and their applications

1. The resource-based view of the firm

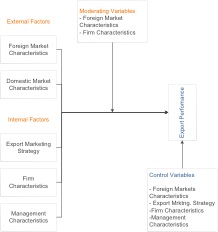

This theoretical perspective emerged during the late 20th century and claims that companies can be seen as bundles of resources, that resources are heterogeneously distributed across companies, and that the market for resources is imperfect (i.e., resource differences persist over time) (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000). These resources include tangible and intangible assets, capabilities, organizational processes, attributes, information, knowledge etc. that are under firm’s control. As a consequence, firms can create and sustain competitive advantage by acquiring and leveraging resources that are valuable, rare, inimitable and non-substitutable (Barney, 2001; Barney, 1991; Grant, 1991). Despite being most widely accepted approach for achieving competitive advantage, it is also criticized as vague in nature when identifying key resources affecting success (Priem & Butler, 2001). Figure 1 shows the theoretical framework of the approach.

2. The organizational capabilities approach

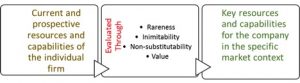

This theory opens up the “black box” of resource-based view and explains how resources and capabilities create value and facilitate competitive advantage for firms. Barney (2001) states: “resources are considered valuable if they contribute to either differentiation or cost advantages for a firm in a certain market context.” The term ‘capabilities’ refers to the firm’s capability to distribute and re-assemble its resources to improve productivity (Makadok, 2001) and realize its strategic goals (Teng & Cummings, 2002). Figure 2 shows the theoretical framework of the approach. Korhonen and Niemela (2005) further strengthened this theory by providing a useful overview of the major differences between resources and capabilities:

- Whereas resources are either tangible or intangible, capabilities combine both: capabilities are clusters of tangible, input resources and knowledge based, intangible resources.”

- “Unlike resources, capabilities have an operational, process dimension – they are not factor stocks, but they are factor flows: capabilities present what a firm can do, they are activities, organizational rather than individual skills.”

- “Capabilities often take a routine-like form and are path-dependent: if a company were to be dissolved, its capabilities would disappear as well.”

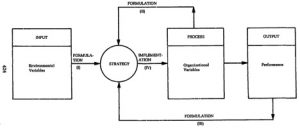

3. Strategic Fit and contingency perspective

This theory of business policy design is based on concept of matching organizational resources with the corresponding environmental context (Chandler, 1962). According to this perspective, market competition and technological development continuously erodes key success factors of an industry. Thus the firm would eventually lose its value over time. Collins (1994) recommended the constant renewal of competitive advantages of the firm making the firm an adaptive system evolving to environmental change. Accordingly, in addition to achieving a strategic fit with present conditions, companies must simultaneously aim for strategic fit of tomorrow, that is, they must develop a feedback mechanism to adapt and learn. Figure 3 shows the theoretical framework of the approach.

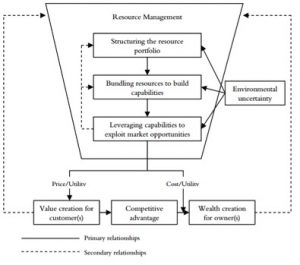

4. The dynamic capability view

This theory builds on the adaptive nature of contingency perspective and suggests that cross-functional capabilities in a firm are dynamic in nature. According to Eisenhardt and Martin (2000), Dynamic capabilities “create value for firms within dynamic markets by manipulating resources into new value-creating strategies”. These capabilities developed through learning mechanisms help the firm in not only achieving differentiation and/or cost leadership but gives it the potential to continuously reinvent. The details of a dynamic capability are often idiosyncratic and pathdependent, but the main features are more common (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000). This theory attempts to prepare the firm for volatile market conditions by enhancing its existing resources and competitive advantages. Figure 4 shows the theoretical framework of the approach.

Creating value is inherent to every firm while translating available inputs to desired outputs. But value creation is never easy. Customers can learn and change without warning, competitors can take over with something of better value. The suppliers would want to increase their bargain power. Changing demographics, economic and technological conditions and unforeseen catastrophizes can undermine any competitive advantage of the firm. To summarize, it is important for the firm to develop sustainable strategies in order to sustain volatile market conditions and maintain its competitive advantage. Strategy is about when and where to go and how to get there in the best way. The theories introduced in this article are amongst the most commonly employed for strategic management by businesses all around the world. It is the firm’s responsibility to put these theories to practice based on its product range and market segment, The management should also include product development and resource management decisions into the long term strategy design when translating these theories to principles and practice.

References

- Amason, A. C. (2011). Strategic management: From theory to practice. New York: Routledge.

- Andrews, K. R. (1987). The concept of Corporate Strategy. Homewood, IL: Irwin.

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 99-120.

- Barney, J. (2001). Is the resource-based view a useful perspective for strategic management research? Yes. Academy of Management Review, 41-56.

- Chandler, A. (1962). Strategy and structure: chapters in the history of American enterprise. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Collis, D. (1994). Research note – how valuable are organizational capabilities. . Strategic Management Journal, 67-73.

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic Capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal, 1105-1121.

- Gilbert, D. R., Harlman, E., Mauriel, J. J., & Freeman, R. E. (1988). A logic for Strategy. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Publishing.

- Ginsberg, A., & Venkatraman, N. (1985). Contingency Perspectives of the Organizational Strategy: A Critical Review of the Empirical Research. The Academy of Management Review, 421-434.

- Grant, R. (1991). The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: implications for strategy formulation. California Management Review, 114-135.

- Hofer, C. W., & Schendel, D. (1978). Strategy Formulation: Analytical Concepts. St. Paul: West Publishing.

- Hoskisson, R. E., Hitt, M. A., Ireland, R. D., & Harrison, J. D. (2008). Competing for Advantage (2nd ed.). Mason, OH: Thomson/South-Western.

- Makadok, R. (2001). Toward a synthesis of the resource-based and dynamic-capability views of rent creation. Strat. Manage. J., 387-401.

- Ohmae, K. (1987). The Mind of the Strategist: The Art of Japanese Business. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Priem, R., & Butler, J. (2001). Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management reserach? Academy of Management Review, 22-40.

- Sirmon, D., Hitt, M., & Ireland, R. (2007). Managing firm resources in dynamic environments to create value: Looking inside the black box. Academy of Management Review, 273-292.

- Stendahl, M. (2009). Product Development in the Wood Industry (Doctotal Thesis). Uppasala: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

- Teng, B. S., & Cummings, J. L. (2002). Trade-offs in managing resources and capabilities. Acad. Manage.Executive J., 81-91.