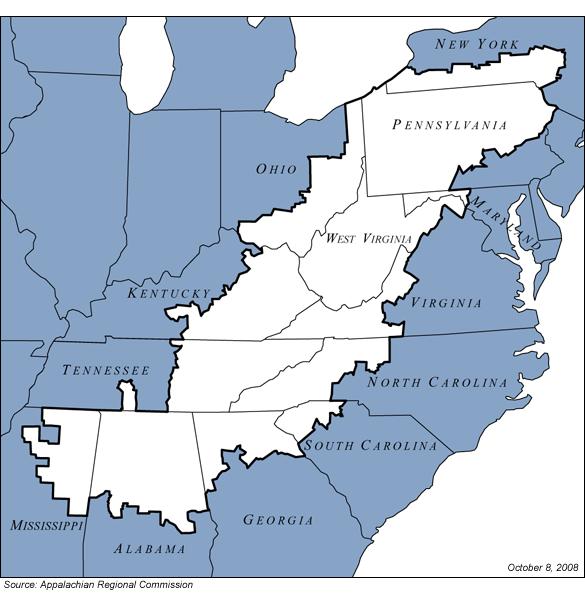

The Appalachian region consists of 205,000 square miles from southern New York to northern Mississippi, also including Pennsylvania, Ohio, Maryland, West Virginia, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Georgia, and Alabama (Figure 1; Appalachian Regional Commission 2010). The economy in this region was fueled historically by forestry, mining, farming and industry and currently, the region is primarily involved in a mix of manufacturing and service industries (Appalachian Regional Commission 2010). Because of diversifying the economy, the amount of distressed counties in the region has been reduced from 223 in 1965 to 82 counties in 2010 (Appalachian Regional Commission 2010).

The manufacturing of forest products in this region is an essential sector of the economy employing over 1.1 million people (Murphy et al. 2008; NC-IOF & NCFA 2003; NESFA 2001; SCFC 2006; Ammerman Unknown Date; PFPA 2005; Young et al. 2007; VDACS 2008; Childs 2005; EDPA 2010; Ervin et al. 1994, McClure 2008, Mississippi State University 2010). An increase in global competition has caused the decrease of domestic markets for U.S. furniture and this increase of competition has taken a toll on the Appalachian hardwood lumber industry (Bowe et al. 2001). The forest products industry in the Appalachian region must be innovative in their marketing strategies to find potential markets for their products (Naka et al. 2009). Other factors affecting the forest products industry has been urbanization, land development and population growth that have decreased the amount of timber available to the forest products industry (Young et al. 2007).

The hardwood industry in Pennsylvania is the top producer of hardwood lumber in the country manufacturing 10% of the total production in the United States (PFPA 2005; Smith et al 2003). Alabama ranks number two in timberland resources with 23 million acres of forestland fueling 850 forest product mills (EDPA 2010). Hardwood lumber mills range in size from producing 1 million board feet (MMBF) to over 40 MMBF a year (Smith et al 2004). Some Appalachian mills have increased the amount of value-added products/processes available to customers in order to increase market size and sales. These value-added processes include: kiln drying, custom sorting/grading, S4S, finger jointing, and dimension manufacturing (Smith et al. 2004). Low grade sawlogs and small-diameter logs were not used traditionally in lumber production in the Appalachian region. The introduction of oriented strandboard mills (OSB), parallel-strand lumber mills (PSL) and rotary-cut plywood mills have allowed the forest product industry to expand the use of low grade raw material and make it value-added product (Luppold et al. 1998).

The forests in this region grow a large variety of hardwood and softwood timber species that are harvested for wide assortment of forest products (VDACS 2008). A variety of hardwood timber species primarily grow in the Appalachian region (Table 1). These species are used in many different end-use applications including: pallets, furniture, flooring, cabinets and millwork (Adams 2002; Virginia Department of Forestry 2007).

Table 1. Hardwood Species Grown in the Appalachian Region (Adams 2002, VDOF)

| Common Name | Scientific Name |

| red oak | Quercus rubra & Quercus falcate |

| white oak | Quercus alba |

| hard maple | Acer saccharum |

| soft maple | Acer rubrum & Acer saccharinum |

| black walnut | Juglans nigra |

| yellow-poplar | Liriodendron tulipifera |

| black cherry | Prunus serotina |

| American basswood | Tilia americana |

Softwood lumber species grown in this region include: Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus), and Southern Yellow Pine (Pinus palustris, P. elliotii, P. taeda, P. echinata). These softwood species are primarily used as lumber for construction applications, furniture, cabinets, and other interior uses (Virginia Department of Forestry 2007).

Not only does the forest have a significant impact on the region’s economy but it also helps control water and air quality creating benefits the local communities (Childs 2005; Virginia Department of Forestry 2007). Components of the forest ecosystem work together to reduce the amount of storm water runoff entering nearby watersheds. In urban areas, forests help lower the amount of runoff by collecting it in leaves, branches and soils (American Forests Unknown Date). Forests produce organic compounds that reduce the amount of air pollution in an area. A study in Chicago, Illinois, found that urban trees helped decreased the amount of toxic emissions in the air surrounding the city (Nowak 1994). The Appalachian forests provide a variety of benefits to both humans and the environment. The forest products industry provides to local economies with added jobs and revenues. The forests also provide a renewable resource that can be sustainably harvested.

References:

Please email Scott Lyong at swlyon@vt.edu to request the list of references.