Organized By

- Department of Sustainable Biomaterials at Virginia Tech

Goal

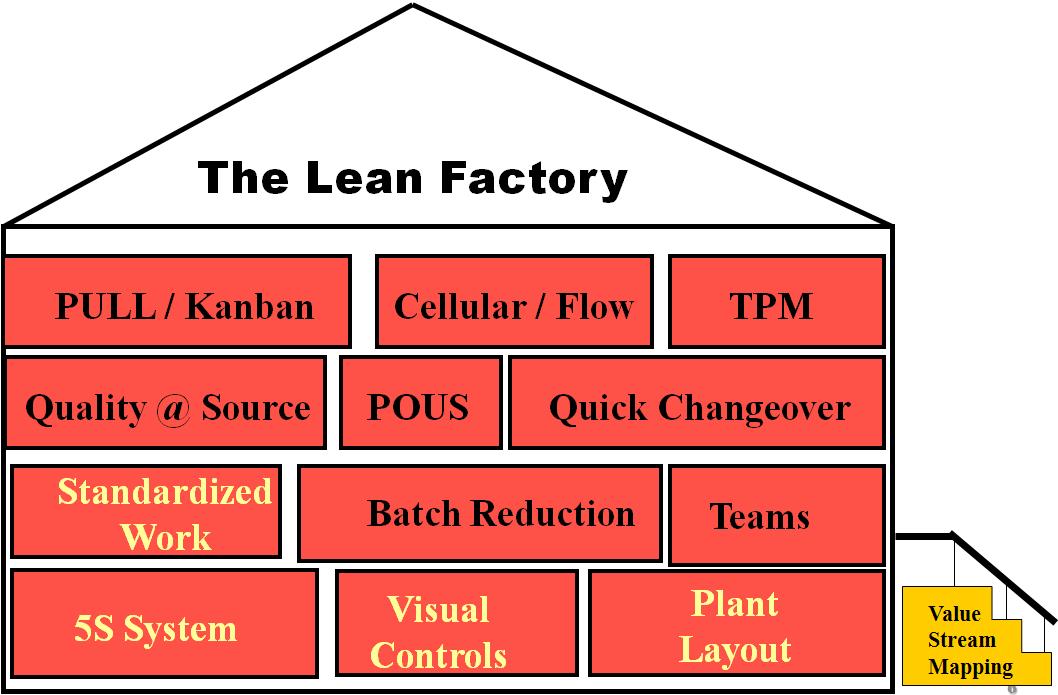

The purpose of this workshop is to inspire new visions and strategies which address the most pressing energy challenges for contemporary society; it will create new ideas for usage of Lean Principles in reducing energy use and costs. It will also promote collaboration between scholars working across disciplines on Lean Thinking and Energy.

Key Values of Workshop

- Attendees will have a better opportunity to understand lean and potential energy savings with the implementation of lean principles into their process.

- Presentation of an Energy toolkit to identify wastes related to energy, environment, and the processes.

- Attendees will be exposed on “How to use Lean principles for Energy Savings” using real applications

- Participants will be introduced to Energy Management Systems and their benefits

Tentative Agenda

September 27, 2012. 9:00 am-4:30 pm.

- Welcome and overview

- Current and future scenaro of Energy in Virginia. Joseph Jones, Director of Executive Affairs. Appalachian Power.

- Lean Thinking Principles. Henry Quesada, Assistant Professor, Virginia Tech

- Break

- Energy Audits using Lean Thinking. Henry Quesada, Assistant Professor, Virginia Tech

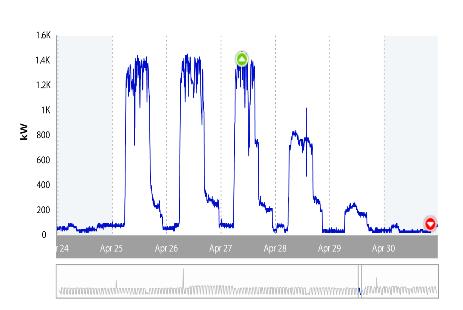

- Energy Management Systems. Tyler Gill, Enernoc Systems

- Lunch

- Industry case study I. Brian Bond, Associate Professor, Virginia Tech

- Industry case study II. Jon Bluey, Building Science Project Manager, Community Housing Partners.

- Closing comments and questions

- Adjourn

Relevant to

- Plant Managers, Quality Engineers, Process Engineers, Procurement Managers, Supplier Chain Managers, Purchasing Managers, Plant Engineers, Energy Managers, Energy and Environment Engineers and Medium Enterprise Manager

- Anybody who is interested in energy savings

Venue

Roanoke Higher Education Center

108 North Jefferson Street Roanoke, Virginia 24016 (540) 767-6100Registration

$50. Includes coffee breaks, lunch, and materials. To register, please follow this link. Please contact Dr. Henry Quesada at quesada@vt.edu if you have any questions or need more details. CEU will be offered for this workshop.

If you are a person with a disability and desire any assistive devices, services or other accommodations to participate in this activity, please contact Dr Henry Quesada at (540 231 0978) during business hours of 8 a.m. and 5 p.m. to discuss accommodations 5 days prior to the event. TDD number is (800) 828-1120.