by Gaurav Kakkar, kakkarg@vt.edu

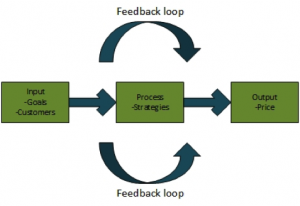

Development of global economy have led to significant increase in the level of globalization. The companies now look at geographical expansion as an opportunity to grow. This also implies that these companies need to prepare themselves for the challenges not seen in the native markets (Lu & Beamish, 2001). The industries thus need to learn and adapt to new culture, environment and markets. The global forest product industry, traditionally evolved to be heavily dependent on locally harvested resources. This gave an advantage to forest-rich regions over the others for potential production and processing installations. The majority of the industries would preferably be located close to the forest due to high transportation and handling costs. Recent advancement in harvest and handling technologies, forest management, expansion of planted forests etcetera have led to a major change in this traditional view. The processing industries no longer have to tie themselves with the close proximity of forest (Bael & Sedjo, 2006). As a result, the forest products industry can now share and impact the globalization. The products and services can now be directed to specific regions of the world where they can be most effective. More and more people across the world can now be benefited from the new and innovative methods. Despite this substantial change, the very nature of wood resource still limits the feasible expansion of this industry.

United States leads global production and consumption of forest products. But this share have been declining since 1990 (Farmer, 2015). This article thus aims to highlight few of the major opportunities and barriers for internationalization of specific product categories in the forest products industries.

Opportunities (Prestemon, Wear, & Foster, 2015):

- The forest management program in the United States assures that the derived products are environmental friendly. This gives industry an added advantage in the markets with growing concern of nature friendly products.

- Asian market has high potential for furniture industry. The U.S. companies can expand and be competitive in this market segment.

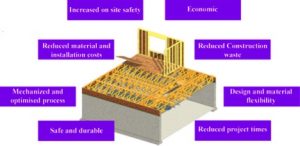

- With positive recovery after the housing decline, the companies can increase investment in this sector. Foreign housing markets can also be explored for expansion.

- Wood pellets manufactured in the U.S. can target the renewable energy market across the world, especially Europe.

- An increase in demand in biomaterials sector for wood fiber is also expected. It includes construction, auto manufacturing and personal care products.

- The timber supply from the U.S. have increased considerably over time and this further will support the comparative advantage in global markets.

- New initiatives to use wood as structural component in tall buildings can open up new market segment for U.S. forest products industry.

Barriers:

Any industry attempting to do business in a foreign market tends to face certain trade barriers. These can be broadly classified into tariff and non-tariff barriers.

- Tariff trade barriers: A tariff (duty) is the tax on the value of product including freight and insurance of imported product levied by the government. The rates depend upon nature of product and vary between countries. Additional taxes (national and local), customs fee are often collected along the tariff at the time of customs clearance. This leads to increase in the cost of delivered good. Most of the U.S. made/originating products can qualify for duty free entry in more than 20 countries that have signed Free Trade Agreements (FTA).

- Non-tariff trade barriers (Sun, Bogdanski, Stennes, & Kooten, 2010):

- Import quotas, export quotas and tariff quotas are some of the most common quantitative restrictions on the volume of different wood products.

- Complexity of licensing procedures, customs, financial transactions act as administrative restrictions and vary from one country to another.

- Different price control measures employed in the target market like custom surcharges, import taxes, minimum/maximum price limits, prior deposits, anti-dumping and countervailing duties.

- Domestic policies aiming to improve the competitiveness of domestic producers in international markets. These include producer or exporter subsidies, financial assistance to domestic industries, tax concessions etc.

- Forest management certification and product labeling to assure that the forest was sustainably managed and is an environmental friendly product is growing to be an important barrier.

These are the few of the key available opportunities and associated barriers that the forest products industries in the United States have to consider while successfully expanding to global markets. Development of new technologies and applications of forest products in this adapting global market can provide a major opportunities to all associated industries.

References

Bael, D., & Sedjo, R. (2006). Toward Globalization of the Forest Products Industry: Some Trends. Resources for the future discussion paper.

Farmer, S. (2015, December 3). U.S. Forest Products in Global Economy. Retrieved from Compass live: Southern Research Station: http://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/compass/2015/12/03/u-s-forest-products-in-the-global-economy/

Lu, J. W., & Beamish, P. W. (2001). The Internationalization and Performance of SMEs. Strategic Management Journal, 565-586.

Prestemon, J. P., Wear, D. N., & Foster, M. O. (2015). The Global Position of the U.S. Forest Products Industry. Asheville: Southern Research Station, USDA.

Sun, L., Bogdanski, B., Stennes, B., & Kooten, G. C. (2010). Impacts of tariff and non-tariff trade barriers on the global forest products trade: an application of the Global Forest Product Model. International Forestry Review, 49-65.